SHA 2013: Preliminary Call for Papers

SHA 2013: 46th Annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology University of Leicester, Leicester, United…

In this week’s #SHA2016 Conference blog post, on D.C. area archaeology, we take a look at Alexandria Archaeology! This is a season of anniversaries as the City of Alexandria’s Archaeological Protection Code recently turned 25! In 2014, the City of Alexandria celebrated the 25th anniversary of the passage of the Archaeological Protection Code, serving as a preservation model for local jurisdictions across the nation.

In 2014, the City of Alexandria celebrated the 25th anniversary of the passage of the Archaeological Protection Code, serving as a preservation model for local jurisdictions across the nation.

The Code has enabled sites that otherwise would have been lost to development to be excavated and studied.

These sites have provided information about the full range of human activity in Alexandria, from Native American occupation through the early 20th century.

The excavated sites highlight the wharves and ship-building activities on the waterfront; the commercial and industrial establishments, including potteries, bakeries, and breweries; life in rural Alexandria; the Civil War; cemetery analysis and preservation; and the lives of African Americans, both free and enslaved.

Over the 25 years the Code has been in effect, the City’s archaeological staff has reviewed more than 11,000 projects that range from building a fence to developing an entire city block, and everything in between. However, formal archaeology did not begin in Alexandria until 1961.

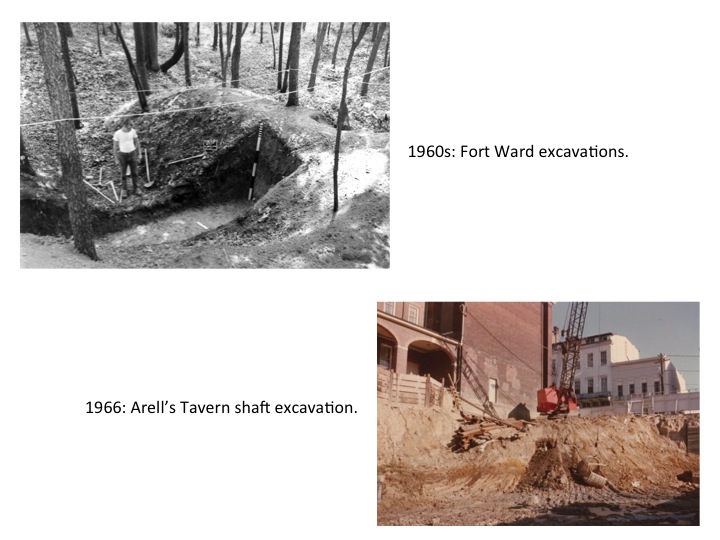

In conjunction with the Civil War centennial, the city took steps to develop a park at the site of Fort Ward, one of the more than 160 forts built by the Union Army to protect Washington, D.C.

Spurred by citizen interest, the archaeological information recovered from Fort Ward led to a reconstruction of its north bastion, as well as the construction of a small museum and visitor center at the park. A few years later, a series of urban renewal projects began along King Street, part of a nationwide trend occurring in many American cities in the 1960s. Buildings that lined the 300, 400, and 500 blocks of King Street were torn down and replaced with newer buildings, and a large market square was built fronting on city hall. Original plans called for 16 blocks to be demolished, but a citizen-led historic preservation movement helped to limit the scale of urban renewal in Alexandria to those few blocks on King Street.

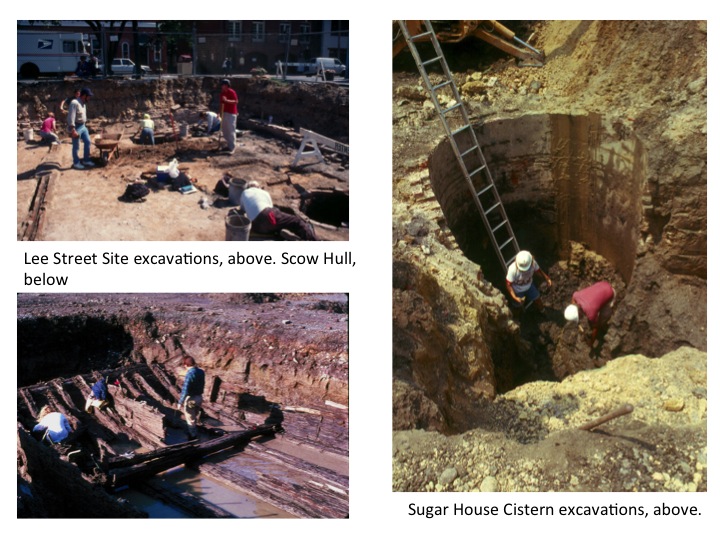

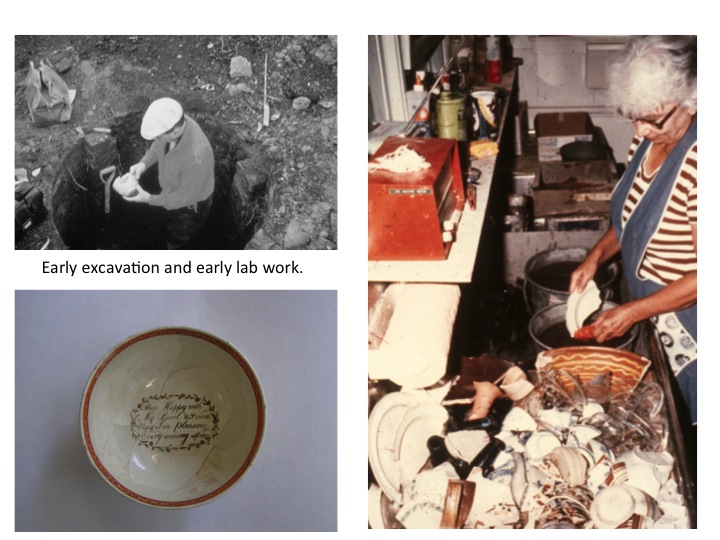

Nevertheless, when the buildings came down, numerous brick-lined wells and privies, as well as deposits of artifacts were visible, and citizens reached out to the Smithsonian Institution to conduct rescue excavations on these blocks. Into the void stepped Richard Muzzrole, a technician with no formal archaeological training, but with an unwavering desire to save as much of the threatened archaeological record as he could.

With guidance from his Smithsonian colleagues, Muzzrole marshalled a small cadre of volunteers and conducted salvage archaeology of the wells, privies, and other archaeological materials uncovered by construction equipment.

Muzzrole established a laboratory for the artifacts in the old Torpedo Factory, which eventually became the iconic Torpedo Factory Art Center. The visibility of the rescue archaeology, and the display of the extensive artifact collections recovered from the King Street wells and privies continued to ingrain archaeology into the civic consciousness. The Smithsonian funded the rescue work from 1965 until 1971. And, for two more years, a group of Alexandrians called the Committee of 100 continued to fund the rescue work with each member pledging $10 per month (today, that would be nearly $60 per month). Eventually, this group actively sought City Council support to include archaeology as a permanent service of the City of Alexandria government. The Council was convinced of the importance of archaeology and historic preservation, and, in 1973, the City began directly funding Mr. Muzzrole and several assistants who worked with the collections. Throughout these years, the display of excavated artifacts, public lectures, and the ongoing rescue excavations continued to forge a public appreciation of archaeology in Alexandria. In 1975, the City established the Alexandria Archaeological Commission, a volunteer citizen group that advises the mayor and Council on issues involving local archaeology and historic preservation- the first organization of its kind in the United States.

The formation of the Archaeology Commission was the first step in professionalizing the practice of archaeology in the city, which in turn led to Alexandria hiring Pamela Cressey as its first City Archaeologist in 1977. Since that time, Alexandria Archaeology has grown from a rescue operation in the Old Town area to a City-wide community archaeology program. Throughout the 1980s development in Alexandria continued at a brisk pace, threatening, damaging, and likely destroying archaeological resources.

Many of the development projects were private enterprises, and did not fall under the federal cultural resource protection laws.

To stem the loss of archaeological sites, the Alexandria Archaeological Commission spearheaded a preservation initiative that culminated in 1989, with the drafting of an archaeological ordinance requiring a five-step review process for all site plans that involve more than 2,500 square feet of ground disturbance.

This Archaeological Protection Code sets out a process whereby the private sector absorbs the cost of archaeological excavation and analysis before ground disturbance occurs on large-scale construction projects. Incorporated into the City’s Zoning Ordinance, the Code requires coordination with other City departments—the planners, engineers, landscape designers, and other regulatory officials who oversee the site plan process. Implementation involves review of all City development projects by staff archaeologists. The staff determines the level of work needed for each project, and, when required, a developer must hire archaeological consultants to conduct investigations of potentially significant site locations and produce both technical and public reports on their findings. From these beginnings, Alexandria Archaeology now manages over 2,000,000 artifacts collected from over 100 archaeological sites scattered across the City.

The collections are open to researchers, and a small sampling of the artifacts are on display for benefit of the public at our museum, in the Torpedo Factory Art Center, alongside 85 studios designed for artist-public interaction. The Archaeology Museum’s glass windows and public laboratory encourage visitors to observe the archaeological process in action.

Numerous research projects are undertaken as well, which include public participation through volunteer work, education in the museum, and outreach activities. Volunteerism is the watchword of Alexandria Archaeology; we could not exist without the contributions of hundreds of volunteers.

More than 100 give of their time and talents in an average year.

One special volunteer still works in the lab after more than 30 years. Volunteers work in all aspects of the program from digging and laboratory work, to education, research, oral history, and editing. In 1986, a group of volunteers formed a 501(c)3 organization, the Friends of Alexandria Archaeology (FOAA). FOAA sponsors events, publishes a newsletter, maintains a website, Facebook page, and Twitter account, and supports the Museum in all its work.

The future looks bright for Alexandria Archaeology.

It has been 50 years since Richard Muzzrole first poked a shovel in a privy on King Street.

Here’s hoping that we have another 50 years in front of us of community archaeology in Alexandria! Please Visit our Website: www.AlexandriaArchaeology.org Friends of Alexandria Archaeology: http://www.foaa.info/

My first historical archaeology field school was with Alexandria Archaeology!